NOT ALL SHADOWS FALL

THE SAME

a conversation between Satu Streatfield

and Casper Laing Ebbensgaard

Casper Laing Ebbensgaard: What are some of the biggest challenges you face through your work as

a lighting designer?

Satu Streatfield: The most interesting challenge

lies in coordinating efforts across public and private land. The majority of the lighting design we see

in cities is private; even some of the lighting that appears public is privately owned and maintained. You can often spot where an area or street falls under private ownership; the lighting is more coordinated, and you get less of that messiness that naturally emerges at night. Private tenants and big landowners and developers in London have the resources and control to implement expansive lighting strategies, so the overtly designed spaces reflect private interests. Essentially, it creates ghettoes of luxury lighting that appear remarkably different to their surroundings. I walked around Stratford the other night and the privately-owned residential developments have bespoke lighting

for each plot. It feels like walking around a lighting showroom or a trade fair, without any continuity. Each one is trying too hard and it ends up creating these weirdly overdesigned and disjointed campuses. It doesn’t feel like London at all to me. Local authorities struggle to afford lighting design beyond basic streetlighting and a number of them are locked into Private Finance Initiative contracts (PFIs) where a contractor implements one-size-fits-all solutions, using standardised streetlighting that floodlight spaces uniformly in the name of safety, security, and risk mitigation. In these types of arrangements, the contractor has no motivation

to tailor the lighting, to think about the character and the experience of the space at night, so it results in over-lit and soulless streets.

CLE: The challenge of balancing the interests of private and public stakeholders obviously requires structural change, but also a much better understanding of how different forms of light correspond with different forms of life at night?

SS: Absolutely, it requires a much deeper understanding of the uses of the city at different times and a much more fine-grain control of the lighting; our lighting systems should be much better joined up. Across the City of London, for example, the local authority has introduced a progressive street lighting control system, which gives them control over each streetlight. Their experimental approach enables them to test and tailor the lighting to respond to the metabolism of spaces.

I went on a tour with their streetlighting engineers one evening when all the bars, offices and shops were packed and they dimmed the streetlights from 100% to zero and no one batted an eyelid. Nobody noticed the streetlights were turned off. It poses the question about how public and private lighting might work better together and with sensitivity towards the uses of spaces. We could get away with reducing public lighting quite dramatically because there is so much streaming from private tenants already. And this is not a new idea: in Medieval London each household was responsible for lighting the space outside their property and streetlights were not turned on during full moon. In town centres its similar. Restaurants, bars, shops and pubs create a series of outdoor rooms that spill

onto the street, encouraging a similar kind of custodianship towards their frontage. We could

do more and think more ambitiously about the potential in that. When I am walking around London at night, it is the glow from windows and building entrances, buses and bikes moving around that makes it so cinematic. When the street lighting

is overly dominant it kills off that vibe.

CLE: So what is the design response to not overdesigning and over-specifying spaces at night?

SS: It is extremely important to knit new developments into their surroundings properly. Often, the visualisations that are produced as part of a design brief fade the context out, creating a black canvas on which the proposed design really stands out. That is obviously very misleading—our perception of light is always relative to context.

We have to think more seriously about context and embrace the messy patchwork of the street scene

as a condition for producing lighting design proposals. This is why the City of London control system is so interesting, because it’s more about how you choreograph that patchwork to maintain

a good balance, almost like a DJ—and less like an architect—creating symphonic cohesion. Allowing the night to breathe a bit.

CLE: Is this not what light master planning aims

at doing, coordinating the transitions between differently lit spaces better?

SS: What makes the image of urban night-time

so special is that it’s an ever-shifting collage

of collective light, where boundaries blur and something else appears. So, the point is that

a huge part of any lighting strategy requires not just suggesting what is lit and how, but getting buy-in from different public and private lighting owners

to better coordinate efforts and be sensitive and frugal with their lighting. People often design in silos without much attention to what’s already there. Lighting designers and engineers spend

hours toiling over achieving certain numbers of illuminance and uniformity, but those numbers never appear in reality because of the light next door. I worked on a lighting scheme for a public square once, which was designed to be lit at very low levels, 2 lux, from one side to allow for a darker and calmer space. When we turned up a giant TV screen had been installed, which flooded the entire space with animated, coloured light.

It is important to develop a more collaborative design approach and a lot of that comes from building more serious partnerships with local stakeholders and fostering a sense of custodianship of public space at night. Whether people go out for leisure, work or whatever, they rely on active spaces to feel safe, and that comes from the inside-out more than during the daytime. I don’t think the solution to ensuring safety and comfort at night

can be done by just adjusting the lighting, lighting up shop windows or leaving hallway lights on.

It needs to emerge through a genuine partnership that configures the nocturnal city as a lived space. All the conflicts that are foregrounded in night-time planning and design, around safety, security, noise complaints, people out getting pissed, you cannot fix through design. You can mitigate, but you can’t solve it.

CLE: Essentially, you’re proposing to move away from lighting design proper to instead thinking about nurturing relations and communal ties as, somehow, bearers of night life?

SS: The idea of designing or curating the urban night with lighting alone is kind of nuts. The idea that you can eliminate deep-rooted problems of social inequality through aesthetic tinkering

is nuts. Lighting design is super important in urban environments, but the end goal is not necessarily what the lighting looks like but the kinds of relations it engenders.

CLE: How does that kind of attention to the night extend into the vertical city? How do you approach verticality it as a designer?

SS: There is a delight in seeing the random occupancy of the upper floors of residential buildings at night. It is one of my favourite urban lighting effects. All these characters revealing themselves in a random array, all stacked on top

of each other without any coordinated effort.

That kind of uncoordinated effort works because

the light is internal and often filtered through curtains, and people don’t light their living spaces like offices or supermarkets, so it gives a much subtler light. And you have different colours, different levels, flickering and moving. It’s just beautiful and the thing about it is that it appears ‘naturally’. The tension between order and disorder incidentally plays out across the façade of the

tower block. But this organic modularity of life

in the heights is under threat from ‘lighting design’ itself. Increasingly, residential high-rise buildings

in London are introducing vertical and horizontal stripes of light on their façades and it feels incredibly contrived—as if trying to make up for

a lack of activity inside. That’s just sad. I think the ability to integrate LED lighting more readily into structures and to accentuate and enhance long, continuous lines is producing some very expensive and equally pointless lighting schemes. Instead of adding lighting to buildings and structures we should design from the inside out, use the interior lighting to create the building image—which is what Richard Kelly did in the 1950s.

But the vertical city is not just residential, the other day I passed a church where someone had whacked a floodlight onto the roof to light the spire, just from that one side. Not the most refined method, but it gave a beautiful, cinematic chiaroscuro effect. More incidental. I enjoy single source lighting for features, because it gives a kind of directionality to the object, like sunlight. In sunlight all shadows fall in the same direction and there is a sense that the light is radiating from a point and fading over distance. In most contemporary architectural lighting, the temptation is to hide LEDs at every level, to describe the architectural design in detail and be faithful to its intended hierarchy. I don’t mind architectural lighting but

I think lighting designers should challenge themselves to use fewer mounting points and fittings, and work with the interior lighting more—think about the lit façade as a backdrop to activity on the street, and an emitter of light through window apertures, rather than describing every detail of an architectural design.

BROKEN LIGHTS

by Casper Laing Ebbensgaard

and Rut Blees Luxemburg

Cities are filled with them. Their ubiquity is testament to their almost faultless performance, functionality and unrivalled durability. And they are remarkably alike. Products of a ‘modernist’ urge for maintaining the semblance of ‘order’ through material consistency. They are products of the powerful principle of standardisation—the uniform appliance of technologies to maintaining a certain level of ‘quality’ across differential space.

Street-lamps, flood lights and bulkheads make up the majority of the lights we encounter in the city, yet often, they get relegated to pure functionality with little consideration of their potential qualities. Maybe that is due, in part, to their serial repetition, inviting comparison and scrutiny of their semblance of seamless application. The very same bulkheads that are mounted on council estates, according to principals adopted from Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, are fixed to the hoardings surrounding construction sites that give rise to the new additions to London’s skyline.

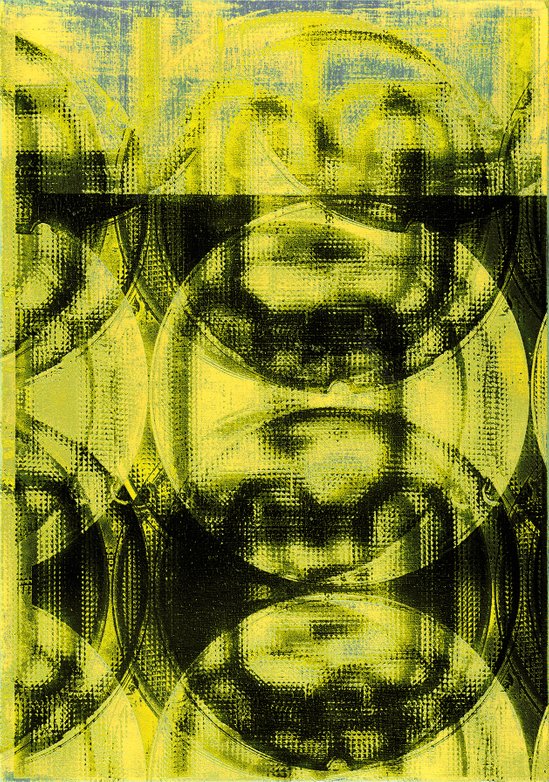

At night the surfaces of the city start to crack,

light seeps through its fissures and leaks through

its crevices. The boundaries that maintain bodies within predictive patterns of movement and mooring are rendered porous and more unstable once darkness falls. The fourth volume of The Dark Preview explores how the encounter with ‘broken’ lights in the vertical city offers a new language for nocturnal illumination that challenges conventional approaches to managing life at night.

Adam Glibbery

Two Palaces

by Jordan Rowe

From the balcony of our ninth-floor flat we stood

in its imposing shadow. In the eyes of a 12-year-old, its cold metal and steel craned over us. A symphony of hostile materials shooting into the sky, adapted and utilised to form a delicate lattice-like pattern.

The Crystal Palace transmitter sits on the ruins

of its namesake—a former palace, nominally created ‘for the people’. Previously hosting the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, the building found permanent residence within the well-to-do south London suburb of Sydenham Hill. Displaying the accumulating wealth of Britain’s empirical pursuits, exhibits would showcase the technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution to a largely aspirational, middle-class audience. The content

was a display of strength and power, wealth and prowess, reflected by grandstanding engineering and spectacular architecture.

Rising from the ashes of the exhibition halls,

the transmitter marked the dawn of another age

of technological and engineering innovation, reaching a height not seen before in the UK and providing new capacity for television broadcasting. Adorned on its skyscraping summit stands

a red light:

a nocturnal warning message to planes and other flying objects to avoid potential catastrophe.

This continual blink proves to be more than a banal piece of practical infrastructure. From the bedroom of the flat I shared with my mum, my window pointed out to the hill it was perched on. Each night I would fall asleep with the transmitter flashing away in the background. Perhaps unsurprisingly

it took on an almost mythical presence in my mind, assuming the role of a guiding star for lost travellers in the deep suburbs. I was one of them.

A boy of mixed heritage, struggling with his sexual identity, looked out upon this adventurous jungle gym and saw a device that could propel him to the peak of the city.

Could it gain him the height necessary for a better perspective on the city, and a chance to identify

a place he could truly feel at home within it?

In spite of the heights of our own vertical residence, my perception of the two spaces couldn’t have been more divergent. The transmitter was a known, yet elusive figure. A critical element in the mechanics

of the city—it was maintained, attended to, and cared for—quite unlike the fading block in which

we resided. The propelling nature of our frequently broken-down lifts soon lost their shine. We were

a relic to the transmitter’s marvel.

High-rises have often been used to project power, and the transmitter was built to be as much

of a statement as the original Crystal Palace.

The transmitter was my palace. Confused by my circumstance and my surroundings, I projected myth and a tropicality upon it. Attractive, yet exclusionary, I could perch on my windowsill with

a lingering curiosity as to what it stood for and what it meant for me. An example of the heights that can be achieved - the ones I would spend my life trying to climb—and a reminder of the heights that are overlooked and undervalued—I was sleeping

in one.